From childhood, Rex was a prolific sketcher. His school notebooks are laced with caricatures of teachers, with demonic figures and satiric commentary, an early hint at the peripheral characters and tone of his own films. Even the schoolboy humour was never quite to vanish as, for instance, the banana skin sequence in The Prisoner of Zenda demonstrates.

In 1912, soon after his arrival in America and still named Rex Hitchcock, the new emigrant enrolled at the Yale School of Art, intending to study sculpture. There he was taught by Lee Lawrie, one of the foremost architectural sculptors of his day, who is now best remembered for his bronze “Atlas” in New York City’s Rockefeller Center. Lawrie was much struck by Rex and the two remained close friends until the latter’s death. Rex never finished his degree – the movies lured him away too early – but in 1921 Yale conferred an honorary degree on their former student in recognition of his achievements on the screen.

Scraping a living in New York after his departure from Yale, Rex hung out with the Bohemian, artistic set clustered around the studio shared by Thomas Hart Benton and Ralph Barton in the Lincoln Arcade. There he met many of the rising actors, artists and writers of the post-war years, including the future art critic Thomas Craven, and Willard Huntington Wright who, as S. S. Van Dine, was the creator of the popular detective, Philo Vance. Another visitor to the studio was William Powell, then appearing on Broadway. Although this group went its separate ways, Thomas Hart Benton and Ralph Barton kept up with Rex who found them both work in the film industry over the years. Much later, Rex would appear fleetingly as the Irish patriot, Charles Stewart Parnell, in Barton’s home movie skit, Camille (1926).

Throughout his Hollywood years, Ingram continued to sketch and to sculpt as time allowed; he also was an art collector and the walls of the Hollywood bungalow in which he later lived were cluttered with paintings, many of them romantic depictions of Arab life by the French Orientalists, including works by Etienne Dinet, Horace Vernet and Théodore Chassériau. In 1934, he allegedly deposited his collection of Arab art with a museum in Cairo.

His own sculptures and sketches are scattered around private collections; see for instance the listing by the Smithsonian.

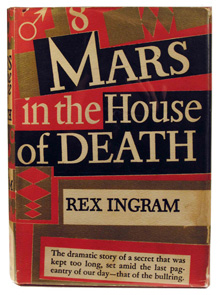

Following his retirement from filmmaking, Rex published two novels, the first, The Legion Advances, appeared as a limited edition in 1934. It’s a blood-and-guts story of the adventures of the French Foreign Legion, dedicated to his friend Marechal Lyautey, the veteran French military campaigner in Morocco. The second, Mars in the House of Death, received much wider distribution on its publication in 1939. A Hemingway-esque tale of a famous bullfighter and his doomed love for the woman who turns out to be his half-sister, Time magazine pronounced it a “colorful, realistic, badly constructed tale …[that] will add more to Ingram's reputation for versatility than to literature."